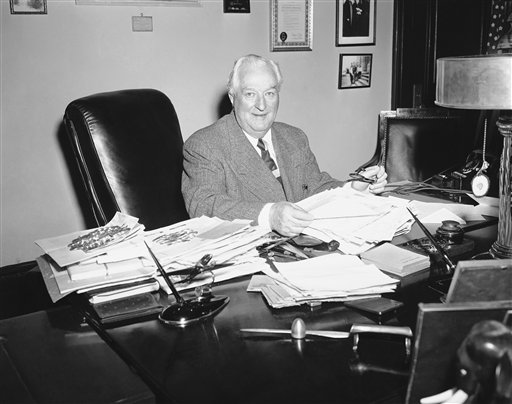

Sen. Pat McCarran (D-Nev) at his desk in 1949 . McCarran was a supporter of Sen. Joseph McCarthy and chaired the Judiciary Committee during the late 1940s and early 1950s, when fear of Communism was particularly rampant. He went on to author the McCarran Internal Security Act of 1950. The act required the Communist Party and the 24 other organizations charged as Communist to register with the Justice Department, but none did. (AP Photo/ Henry Burroughs, used with permission from the Associated Press)

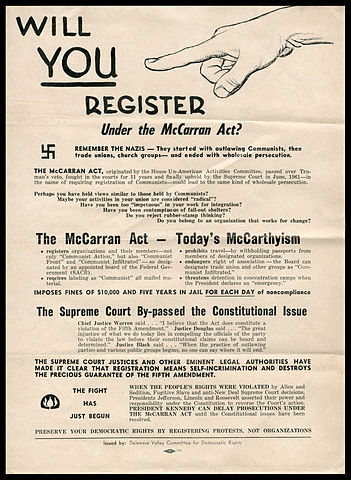

Congress passed the McCarran Internal Security Act of 1950 over the veto of President Harry Truman four months into the Korean War. Critics believed the act posed a risk to First Amendment rights of freedom of speech and association.

The author, Sen. Pat McCarran, D-Nev., was a supporter of Sen. Joseph McCarthy and chaired the Judiciary Committee during the late 1940s and early 1950s, when fear of Communism was particularly rampant.

The act had three main components.

The preventive detention provision was not part of McCarran’s original bill. Its authors, including Democrat Senator Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota, had hoped to sabotage the bill by making it even tougher on Communism. They miscalculated, however; the “poison pill” was accepted.

The act required the Communist Party and the 24 other organizations charged as Communist to register with the Justice Department, but none did.

Congress passed the McCarran Internal Security Act of 1950 over the veto of President Harry Truman four months into the Korean War. Critics believed the act posed a risk to First Amendment rights of freedom of speech and association. The act required associations that the government considered Communist to register with the government and submit information about membership, finances, and activities. (Poster of the Delaware Valley Committee for Democratic Rights, circa late 1961, via Wikipedia, public domain.)

President Truman had vetoed the act because of perceived constitutional problems — problems soon uncovered by the Supreme Court.

Although the Supreme Court in 1961 upheld a SACB order requiring the Communist Party to register, in Communist Party of the United States v. Subversive Activities Control Board (1961), courts later ruled that individual members could not be compelled to register the party. In Albertson v. Subversive Activities Control Board (1965), the Court declared that registration of an individual amounted to self-incrimination and violated the Fifth Amendment.

In Aptheker v. Secretary of State (1964), the Court ruled that denying members of Communist organizations passports was unconstitutional. And in United States v. Robel (1967), the Court declared that a member of a Communist organization who worked for a defense facility and who was indicted because of that fact was being denied his First Amendment right of assembly.

In 1968 Congress removed the requirement that Communist organizations had to register with the attorney general. The SACB had virtually ceased to function, and appointments to the board were viewed as sinecures. The SACB was authorized only to maintain a public list of organizations and individuals it found to be communist.

The preventive detention provision was repealed in 1971. It had been opposed by organizations of Japanese Americans, who had been relocated from the West Coast and detained in camps during World War II.

In 1972 Congress slashed the SACB’s budget by 50 percent, and President Richard Nixon’s 1973 budget message omitted all funds for it. The board had ceased its operations by 1973.

Then in 1993 Congress repealed much of the act (Sections 1, 3, 5, 6, 9–16). By the 1990s, the Communist threat was no longer relevant.

This article was originally published in 2009. Martin Gruberg was President of the Fox Valley Civil Liberties Union in Wisconsin. Dennis Miles is a reference and instruction librarian at Texas Wesleyan University.